|

|

This

lovely Irish Page is edited by Carole!

Thanks, Carole!

I know she'd love to hear from you :-)

Irish History

and Lore

St.

Patrick

The

Shamrock

The

Claddagh Ring

Leprechauns

and Cluricauns

Celtic

Customs on Death

The

Flag of Ireland

Irish

History in Maps

The Irish Pioneer

Irish

Participation in the Civil War

The Potato

Famine

Irish Songs

United

Ireland

Influential

Irish Americans

Michael

Collins

Patrick

Kennedy

Poems

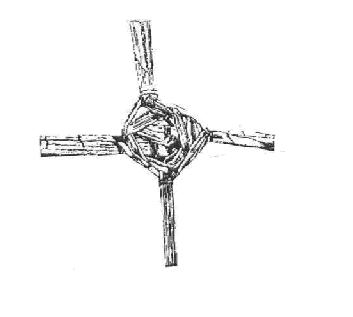

Irish Craft of

Samhain Parshell

Recipes

Meats

Seafood

Vegetables

Soups

Breads

Sweets

Beverages

Saint Patrick: Saint Patrick was born in England around 389AD. Taken from his farm home at age 16 by Irish raiders, he was sold into slavery in Pagan Ireland. Six years later he escaped and returned to his home in England. While in Ireland, Saint Patrick found his faith in God. Patrick decided to study for the Priesthood. Around 432AD. Saint Patrick went to Ireland and established churches in both the North and West. He also established the Episcopal See in Armagh, Ireland. He established many monasteries for both men and women, and made Ireland famous for learning and religion. Patrick died on March 17th 461 AD in County Down, Ireland.

The Shamrock: The Shamrock, at one time called “Seamrog” symbolizes the cross and Blessed Trinity. Before the Christian era it was a sacred plant of the Druids of Ireland because it’s leaves formed a triad. The well known legend of the Shamrock connects it definitely to Saint Patrick and his teachings. Preaching in the open air on the doctrine of the trinity, he is said to have illustrated the existence of the “three in one” by plucking a Shamrock from the grass grown at his feet and showing it to his congregation. The legend of the Shamrock is also connected to the banishment of the Serpent Tribe from Ireland by tradition that snakes are never seen on a trefoil, and that it is a remedy against the stings of Scorpions and Snakes. The Trefoil in Arabia is called “Shamrakh” and was sacred in Iran as an emblem of Persian Triads.

The Trefoil, as noted above, being a sacred plant among the Druids, and three being a mystical number in the Celtic religion, as well as all others, it is probable that Saint Patrick must have been aware of the significance of his illustrations.

The Claddagh Ring: The Claddagh ring originated in a small fishing village in Galway city, Ireland. One Richard Joyce, a native of Galway, was being shipped by sea to be sold as a slave to the West Indies plantation owners. However, the seas weren’t safe, and he was captured by a band of Mediterranean pirates and sold to a Moorish goldsmith who taught him the craft of goldsmithing. The year is now 1689. Joyce is released and returns to Galway and then sets up shop in Claddagh where he designs this terrific ring. Everybody loves it. All of Ireland wants one of these rings. As the years pass, the great Famine of 1847-1849 causes a mass exodus from the West, and with that exodus spread the fame of the Claddagh ring. These rings were kept as heirlooms, passed on from mother to daughter. It was not till the high scale production techniques of today that everyone could be the proud owner of one of these magnificent rings. Today, the ring is worn throughout Ireland, and this is the way to wear it.

1 - On the right hand, crown in heart out, the wearer is a single person

2 - On the right hand, crown out heart in, the person is spoken for

3 - On the left hand, heart and crown out, person is happily married

Leprechauns and Cluricauns: The leprechaun is a solitary creature avoiding contact with mortals and other leprechauns – indeed the whole fairy tribe. He pours all of his passion into the concentration of carefully making shoes. A leprechaun can always be found with a shoe in one hand and a hammer in the other.

Most leprechauns are ugly, stunted creatures, not taller than boys of the age of ten or twelve. They are broad and bulky, with faces like dried apples. They have a mischievous light in their eyes and their bodies, despite their stubbiness, usually move gracefully. They possess all the earth’s treasures, but prefer to dress drab. Usually grey or green colored coats, a sturdy pocket-studded apron, and a hat – sometimes green or dusty red colored. They have been known to be foul-mouthed and they smoke ill-smelling pipes called “dudeens” and they drink quite a bit of beer from ever handy jugs. But the other fairies endure them because they provide the much needed service of cobblery.

Leprechauns guard the fairies’ treasures. They must prevent its theft by mortals. They alone remember when the marauding Danes landed in Ireland and where they hid their treasure. Although they hide the treasures well, the presence of a rainbow alerts mortals to the whereabouts of gold hordes. This causes the leprechauns great anxiety – for no matter how fast he moves his pot of gold, he can never get away from rainbows.

If a mortal catches a leprechaun and sternly demands his treasure, he will give it to the mortal. Rarely does this happen.Occasionally, especially after a wee too much beer, he will offer a mortal not only a drink, but some of his treasure. Female leprechauns do not exist.

Clauricans: There is much debate over whether clauricans are actually leprechauns or their close cousins. Except for a pink tinge about the nose, they perfectly resemble leprechauns in all their physical characteristics. But they never wear an apron or carry a hammer, nor do they have any desire to work. They have silver buckles on their shoes, gold laces their caps and pale blue stockings up to the calves. They like to enter rich men’s wine cellars, as if they were their own, and drink the casks dry.

To amuse themselves they harness sheep and goats and shepherd’s dogs, jump from bogs, and race them over the fields through the night.

Leprechauns sternly declare that clauricans are none of their own. But some suspect they are really leprechauns on a spree, who, in the sobering morning, deny this double nature.

Celtic Customs on Death: As the ancient festival of Samhain was held in honour of the Sun God’s death and transition to the dark lands of Under wave where he then resides as Lord of Death, this is the time that the old Celtic peoples came to terms with death and pondered on their own meeting with the Dark Lord. Like all other pre-Christian peoples they had customs surrounding this inevitable part of life. Some of these Celtic customs and burial rites still can be seen today in Christianised forms, while others may seem strange to our times.

Many superstitions and taboos that are still held today in Celtic parts of the country surrounding the deceased have their origins far back in Pagan times. One example of this is the custom of burning candles day and night until the funeral harks back to the belief that the demons of the darkness could be held at bay by the power and light of fire. In Pagan times the dead were washed using water from a sacred well or by sea water to protect them while passing through the realms of water to the land under wave (Ti r-fo-Th on n).

When washed the corpse was wrapped in the Eslene (Death Shirt) and laid on a fuat or bier in the centre of the home for seven days. Rush torches were kept burning for seven days and nights. The rites would begin by the traditional practise of ‘Caoine” (pronounced Keena, the anglicised word became keening). This would take the form of great lamentation interspersed by periods of praise for the dead person. After three days of Caoine and dependant on the status of the deceased, feasting and games would be held in their honour, the corpse having a bowl placed on their chest filled with food, and gold and weapons etc. were laid out on the bier. This would continue till the day of internment or cremation in some places.

Under Brehon Law there existed the “rights of the corpse”, this law stated that certain personal possessions belonged to the dead and could not be taken from them under any circumstances, even as a debt owed. These items were a horse, a cow, a bed, a house or its furniture. (Considering modern law on this matter how can we call these people Barbaric?) These items would be retained by next of kin.

On the morning of burial a visitor came bearing a measuring rod called a “fey”. This rod, made of Aspen and carved with Ogham letters and symbols, was used to measure the deceased to ensure a proper fit within the final resting place. The mourners would avert their eyes from this rod in awe and terror, it was thought that if this rod caught your measure your death was inevitable. Finally at the setting of the sun on the seventh day the corpse would be carried by seven men or a chariot if of noble status and buried or burned depending on tribal custom.

The tricolour national flag is the tricolur of green, white, and orange. The flag is divided into three equal stripes and its width is equal to twice its height. It is used as the civil and state flag and as the civil and naval ensign. The green stripe represents those native Irish descent, the orange stripe represents the

descendants of 17th century British colonists, and the white stripe represents the hope for peace between the two groups.

Soldier's Song

(Ireland's National Anthem)We'll sing a song, a soldier's song,

With cheering rousing chorus,

As round our blazing fires we throng,

The starry heavens o'er us;

Impatient for the coming fight,

And as we wait the morning's light,

Here in the silence of the night,

We'll chant a soldier's song.Soldiers are we whose lives are pledged to Ireland;

Some have come from a land beyond the wave.

Sworn to be free, No more our ancient sire land

Shall shelter the despot or the slave.

Tonight we man the gap of danger

In Erin's cause, come woe or wea;

'Mid cannon's' roar and rifles peal,

We'll chant a soldier's songIn Valley green, on towering crag,

We'll chant a soldier's song

Our fathers fought before us

And conquered' neath the same old flag

That's proudly floating o'er us.

We're children of a fighting race,

That never yet has known disgrace,

And as we march, the foe to face,

We'll chant a soldier's songSons of the Gael! Men of the Pale!

The long watched day is breaking;

The serried ranks of Inisfail

Shall set the Tyrant quaking.

Our camp fires now are burning low;

See in the east a silv'ry glow,

Out yonder waits the Saxon foe,

So chant a soldier's song.

If legend is to be believed, the first Irishman to see the New World's shoreline was Saint Brendan the Navigator, whose fearless journeys in the fifth century A.D. may have taken him as far west as North America. Whether or not he actually beat Columbus by nearly one-thousand years or not, his exploits were remarkable. If, in fact, Saint Brendan’s story is more legend than fact, then William Ayers probably was the first Irish person to see the New World. A native of County Galway, he served as a crew member on Christopher Columbus’s historic journey across the Atlantic in 1492. Whatever the truth, it is a fact that the Irish were a presence throughout the English-sponsored colonial settlements that began with the founding of Jamestown. Protestant Irish were part of America’s inital rugged frontier dwellers, scorning the cities that were home to the Anglo-Irish who fit in so easily with the Yankee. In the hollows of Kentucky, where Daniel Boone’s Ulster-immigrant family settled, and the rugged terrain of the Blue Ridge Mountains where Tennessean Davy Crockett rose to fame, the Ulster Irish carved out a life far from mainstream colonial America.

It was the Ulster Irish who provided the backbone of the ragged rebel army that took on the forces of the Crown, beginning with the first shots at Lexington and Concord in 1775. A British colonial official in America reported back to London that, “emigrants from Ireland are our most serious opponents”. Irish heroes were plentiful during the war, prom Henry Knox, descendant of Ulster Protestant settlers, who went on to become the nation’s first secretary of war, to Commodore John Barry, a Catholic immigrant who founded the United States Navy.

In 1790, the US Government first census found 44,000 Irish immigrants among the new nation’s 3 million people and another 150,000 people of Irish ancestry. Half of the total lived south of Pennsylvania. Many historians put the figures as far too low. The Catholics in America in those days estimated 35,000 Catholics. It’s clear that the dominant Irish experience in Revolutionary America was Protestant. All told, about a million Irish came to America between 1815 and the Famine, and they did so in waves. Early on, many of the immigrants were middle class Ulster Protestants, but later as the need for labor outstripped the supply, thousands of unskilled, poor Irish Catholics began to cross, ready to wield a shovel and pick and go to work on America’s canal system. By 1838, Catholics were the dominant immigrant group, and by 1840, half of all immigrants were Irish. Their poverty foreshadowed the great multitudes that would wash ashore when the potato fields failed, and the conditions in which they lived offered hints of the horror to come. Cities throughout the North found themselves host to small shanty settlements referred to as “Irishtowns”, a term devoid of affection. Jobs were not hard to come by, but they were needed if the American republic was to achieve its manifest destiny - a term an Irish American journalist named John L. O’Sullivan coined in 1845, as pre-civil war America set its sights westward.

Ireland, a nation on the eve of starvation was about to turn its eyes westward too. But, its destiny was uncertain at best.

More than 170,000 Irish Americans fought under the flag of the United States between 1861 and 1865 during the Civil War. People in the United States were very anti-Catholic up to that time. There were around one-million Irish-Catholics in the United States in 1861.

When the Civil war began in April of 1861, after the Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter, South Carolina, forces of men were collected from Washington, D.C., Richmond, Virginia and the decision was made to form an “Irish Brigade” for government service. They were to be known as the “Wild Geese”. The commander was Thomas Francis Meagher. Most of the Brigade members were both Irish and Catholic.

Their achievements in the Brigade were seldom acknowledged in the Irish-American Community. The Brigade wanted to advertise the important contributions to the Union cause that Irish Catholics made. The founders of the Brigade wanted to show the unsure Americans the important contributions to the Union cause Irish Catholics made, and the devotion Irish Americans felt for their adopted land.

The Irish Catholics knew the prejudices they had faced in America and were not in favor of President Lincoln’s beliefs in the 1850’s, however, they would “stand by the Union, fight for the Union; die for the Union.”

The Irish hostility to Britain also contributed to their support for the Union. Many believed that a break-up of Union would increase British power in the world, so the Irish supported the Union. Many Irish joined simply because they could not find work and the army was a way to ward off starvation.

The Battle of Gettsburg was the worst period for the Irish Brigade, It lost 75% and was down to 200 men. The Irish, however, remained with the Union and through hard fighting under Grant took part at the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865.

During 1863 it became very difficult to recruit new members for the Irish Units and most Irish leaders had turned against the War. Washington’s purposes included freedom for the blacks, an issue that Irish-Americans could not support with the same enthusiasm they had in defense of the Union.

The New York draft riots of 1865 brought to a boil the simmering Irish resentment at sacrificing their lives for the advancement of their hated black adversaries. Many Irish-Americans did enlist and fight in the Union army, but their numbers and spirit matched the early days of the war.

In 1840 there were more than 8 million people living in Ireland, an island about the size of Maine. Most were poor farmers who could not afford to own their own land. They raised crops of wheat and barley, which they used instead of money, to pay rent to their rich landlords, many who lived across the sea in England. To make sure there would always be enough crops to pay the rent, the Irish peasants almost never ate the grains they grew. Instead, they lived exclusively on a diet of potatoes.

In 1845, a terrible disease hit the Irish potato crop. Potatoes rotted in the fields, and a sickening stench was released across the countryside. the disease spread. People tried everything they could think of to combat the disease. They would boil the potatoes and treat them with salt; soak them in bog water and expose them to poisonous gas. Nothing worked. The disease quickly spread and people starved to death. Thousands of farmers ate their crops; they could not pay rent and were evicted. Many were homeless and without job skills. Without homes people lived in ditches and caves, they slowly became weak from hunger and disease and finally would die. For 5 years the potatoes rotted in the fields. The famine was a national disaster for Ireland. Entire families were killed, villages stood abandoned, and dead bodies littered fields and roadsides. Bodies were put in wagons and placed in pits because they had no money for a proper burial or the strength to dig a grave. More than 1 million Irish died of starvation, hunger and related diseases during the Great Potato Famine. Millions more left Ireland. It took many years for Ireland to recover from the damages of the Famine.

The Irish have not forgotten the ordeal their ancestors suffered many generations ago, and to this day the legacy of the “Great Potato Famine” lingers.

I see the heather blooming,

Across the countryside.I can see the tiny shamrock

Burst forth in all its pride.The hills and fields have come to life

And everywhere things are green.

This my view of Ireland,

So quiet and serene.But, what is that off to the north?

A rumbling sound I hear.

I feel the earth a shaking,

And it fills my heart with fear.Oh, I hope no Irish blood is spilled,

No home is filled with greed.

O think of violence in a land so fair,

Is nearly beyond belief.Sure, you want your nation to be whole;

One Ireland, proud and true.

But, there must be another way;

Something else that you can do.It happened all so long ago

That the strangers came and stayed.

And settled down on Irish lands,

For which they had not paid.Though your loyalties be different,

In affairs of church and state,

I am sure that to a single man,

You want Ireland to be great.But, greatness will not come about

In a land of useless strife.

It will take much understanding

And a deep respect for life.So, tear down your bloody barriers.

Let your children play.

Then Ireland will be united,

In a real and lasting way.

Born Michael Collins on October 18,1890 in Cork, little did anyone know the impact he would have on twentieth century Ireland. While employed as a clerk in London, a friend persuaded him to join the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) a secret group who’s purpose was to make Ireland a republic. Michael soon made a name for himself as a good organizer and did well with finances.

After he proved himself a ruthless revolutionary leader, he became the president of the IRB’s Supreme Council, a position that along with his determined will would make him a major influence behind the campaign against England. He was the driving force that brought together the Irish Volunteers and the IRB to form the IRA (Irish Republican Army). The IRA was very powerful and a strong driving force against the English.

In 1916, after his part in the Easter rebellion, he was incarcerated. Upon his release he joined the Sinn Fein, the Politician party that favored independence.

It was in 1921 he organized the guerrilla warfare that succeeded in forcing Great Britain to sue for peace. Michael Collins became a fugitive and may people helped him hide. While in hiding, he was elected to serve as finance minister to the Sinn Fein revolution Parliament.

Michael was sent to England along with Arthur Griffiths, another leader, to help negotiate the Anglo-Irish treaty. Much of the groundwork had been previously set. After months of negotiations, which Michael went beyond the ground rules that were set, the Irish delegates were threatened with “immediate and terrible war” if they didn’t agree to the terms that started all Ireland to be free except County Ulster.

The treaty was signed on December 6,1921 and the signers from both sides knew the treaty would provoke fierce apposition in Ireland.

Michael Collins said “although the treaty didn’t make all Ireland free of British Control, it was a step toward liberty.”

When the treaty was accepted by the Irish Parliament many walked out in protest. Dissension among Sinn Fein because of the treaty caused many battles called the “Irish Civil Wars.” During this period many felt Michael Collins betrayed them by signing the treaty. He received a great many death threats.

One threat proved fatal. He was shot in the head and died in August, 1922 at the age of 31. When his death became known a thousand IRA prisoners knelt and recited the Rosary and prayed for his soul, spontaneously.

Tens-of-thousands of men, women and children lined up to see Michael Collins for the last time and pay their respects in City Hall next to Dublin Castle. Even British Soldiers, once his enemies, were lined up to pass Michael’s coffin.

On August 28, 1922 over 500,000 people of both sides came together to grieve his passing.

The man who worked and served Ireland to the BEST of this ability finally got his wish, if only for one day. The violence ended, both sides were together,if only for one day, Ireland was at peace, UNITED.

In 1849, with hundreds of thousands of his countrymen already departing for America, Patrick Kennedy made his fateful decision to leave Ireland and his family and take his chance in America. Patrick felt he had nothing to loose. The thatched-roof cottage and tewnty-five acre farm he was to leave behind, offered nothing but continued misery and poverty, if not hunger. Misfortune indeed, alrady had visited the Kennedy household. Patrick’s older brother John died at a young age, long before the Famine and the mass exodus.

Overseas travel was an unknown luxury for the great masses of ordinary people, and the Kennedy family was in no way extrodinary. When Patrick said farewell to his family, he knew it was to be forever.Years later such leavings were called “American Wakes”. nearly as tragic and final as actual deaths.

From Ireland, Patrick’s joumy required a detour to Liverpool, and then on to the United States. During most of the Famine years, it was cheaper to sail to Canada, and thousands took the advantage of the lower price with the intention of immediately pressing on to the United States. Some had no choice but to sail to Canada first because, their landlords booked them on old unfit vessels.

Patrick Kennedy’s month long crossing and introduction to urban America was so different from the rural farm in Ireland. While on board the Washington Irving, Patrick met a young woman named Bridget Murphy, who was two years his junior. Like Patrick she was born in County Wexford. It’s hard to imagine a romance blossoming in the wretched conditions of the ships, but it did. Shortly after their arrival, Patrick and Bridget married and set-up housekeeping in the Irish ghetto of East Boston, a place where it was said “children were born to die here.

Patrick and Bridget settled into their new life amid the crowded, teeming slums to which the Irish were confined. Patrick took-up the cooper’s trade and Bridget gave birth to foui children within eight years. The world in which the Kennedy children were born was appalling. Within months of Patrick and Bridget's arrival, a cholera epidemic swept through the Irish slums, killing more than five hundred immigrants and their children.

Patrick and Bridget became parents for the fourth time in 1858. They named their son Patrick Joseph Kennedy. Ten months later Patrick Sr. came down with cholera and died. He was just 35 years old. The family managed to survive, and joined the ranks of many Irish households that were headed by women.

The young Patrick Joseph put money aside from a job he had on the Boston docks and eventually was able to open a saloon, it was a short journey from that saloon into politics.

Later when Patrick Joseph Kennedy married, he broke with tradition and named his son Joseph Patrick Kennedy . (Most Irish named their children after their fathers or family members)

The Kennedy’s expunged the memory of famine and poverty with great success. A century and a year separate the day Patrick Kennedy died of cholera from the day his Great-Grandson John Fitzgerald Kennedy took the oath of office as our thirty-fifth President of the United States.

Actors:

George M Cohan

Victor Herbert

Eugene O’Neill

Spencer Tracy

James Cagney

Bing Crosby

Gene Kelly

Maureen O’Sullivan

Grace Kelly

Jason Robards

Helen Hayes

Federic March

Gracie Allen

Malachy Mc Court

Mia Farrow

George Clooney

Ellen Burstyn

Carroll O’Connor

Irene Dunn

Audie MurphyAmerican Architecture:

Louis H. SullivanWriters:

Dennis Duggan

Pete Hamill

F. Scott Fitzgerald

John O’Hara

Dennis Leary

Pete Hamill

Williman F. Buckley

Peggy Noonan (from N.J.)

James Joyce

James Farrell

These are Irish Poems and they are by a friend named Robert Farrell

whom I met last year at The Hibernians Saint Patrick Day Party.

The Immigrant Colored lights on the water

Yellow, green and red

Shimmer in the darkness

And beckon to come ahead.On to a brighter tomorrow

On to a life anew

On to the life I long for

In the land of the red, white and blue.There, free air will flow about me

And no longer will I fear

And when someone says things I feel,

I'll stand right up and cheer.At night I'll sleep in safety

And by day I'll do my part

And if this land should need it,

I'll gladly give my heart.I'll study very, very hard

Until that hapy day,

When I can proudly tell the world

I'm a citizen of the USA.

Faiths Uncommon There are soliders on the roof tops

And soliders in the street.

There are soliders on the corner

Where old friends used to meet.Their guns are at the ready,

But their hearts are filled with dread.

They know they are the enemy

And tomorrow may be dead.One thing they know for certain,

That the Irish will not cease.

Until Ireland is one nation,

There never will be peace.The English will not heed their cries

And the Irish will not beg.

So, some Irish tell their story

With the aid of a powder keg.The Violence that they feel forced to do

in and effort to be free

Will leave a scar upon the land

That will be very plain to see.Now, if the English would go their way

And leave the Irish isle,

Then men of faiths uncommon

Would find they've been Irish all the while.

After the Parade The parade was over and bagpipes were still.

Of corned beef and cabbage, I'd eaten my fill.

I drank the green beer and sang old Irish tunes

and listened to jokes about the Quinns and Muldoons.Then, I headed for home and got ready for bed,

But, a vision appeared as I rested my head.

It spoke to me softly in a brogue I knew well.

T'was the voice of my granddad, as clear as a bell.He spoke of old Ireland, her troubles and woes.

He spoke of her struggles against evil foes

and he spoke of her freedom, not yet complete,

For there are foreign soliders patrolling her streets.In his voice there was sorrow and a bit of dismay,

And I felt that I've failed him in some careless way.

Sure, it's great to be Irish and proud as can be,

But, folks need support on this isle' cross the sea.So, when the parade is over and the din seems to cease,

Let's try to remember that for some there's no peace.

But, her day is coming soon she will be

A nation again, united and free.

The Parshell is an important Irish craft as it is the cross which keeps the evil spirits away from your door on Samhain (Halloween) and keeps the barn animals safe the year round. While you want to welcome the good spirits that walk the earth, at Samhain you want to be sure to guard against the bad spirits or the spirits of your enemies! So get the Parshell made and on your door right away!

Materials needed:

1. Two sticks — 1-2 feet long, about 1/2 inch in diameter

2. Tape or string to tie the sticks together

3. Wheaten straw, similar plant material or paper twist (I use green, purple and tan colored twist).Instructions:

1. Fasten the two sticks together securely at right angles to form a cross. (Use tape or string.)

2. If using twist, untwist it and flatten it out but not flat - it should resemble corn stalk/husk.

3. Attach twist or stalks to underside of one of the sticks, or if using straw wedge it under one and over the other stick starting in the center.

4. Moving clockwise, weave the twist or straw over one stick and under the next going around the cross. Stop before you get to the ends of the sticks - a few inches of stick should be exposed.

5. If using twist, try to use two or three colors attaching one to the next as you go.Now you have a finished Parshell. On October 31, place it over the front doorway.

Beef Steak and Kidney Pudding

2 lbs. beef steak

1 tsp salt and pepper

1 lb ox kidneys

1 tbsp flour

1 lb suet paste:

3 cups flour

1/2 lb suet

1 tsp baking powder

Salt

1/2 cup waterChop the suet fine with a little flour. Mix it with the other dry ingredients and add enough water to make fairly stiff dough. Roll out and use at once. Cut the meat and kidneys into thin cubes 1-1/2 inches square. Mix flour, salt and pepper together on a plate and dip each cube into the mixture. Take 1/4 of the suet paste for lid. Roll out remainder to size of baking dish, which must be previously well greased. Line dish with paste, put in meat sprinkling the rest of the seasoning between layers. Leave enough space to admit water to prevent pudding from becoming dry. Fill the dish 3/4 full with boiling water. Put on cover, moisten and seal edges. Tie over scalded pudding cloth. Steamed, cover with greased paper (wax). Let water be boiling. Put in pudding and boil for 3-1/2 hours or steam 4 hours.

Irish Whiskey Sauce

1 Shallot, minced, about 1/4 cup

1/4 cup good Irish whiskey

1 cup heavy cream

2 tbsp Dijon mustard

1/2 tsp salt

1/8 tsp pepperIn a small pot melt the butter over a medium heat. Add shallot: cook until beginning to soften. Stir in whiskey; bring to a boil. Cook until most of liquid evaporates, 2-3 minutes. Stir in heavy cream, mustard, salt and pepper; bring to a boil. Cook stirring occasionally, until mixture thickens and reduces by 1/4; about 4 minutes. Remove from heat. Stir in parsley. Serve with meat.

Irish Stew

1 tbsp oil2 onions, sliced

2 lb stewing lamb, cubed

3 carrots, thickly sliced

2 celery sticks, chopped

1 leek, sliced

1 lb potatoes, thickly sliced

2-1/2 cups water

2 tbsp chopped, fresh parsley

1 tbsp chopped fresh, thyme

1 bay leaf

Salt & pepper to taste

Parsley to use as garnishHeat the oil in a heavy saucepan and fry the lamb until sealed on all sides. Add the onions, carrots, celery, and leeks and fry for 2 minutes. Add the potatoes. Pour in just enough water to cover the ingredients, add the herbs and season with salt and pepper. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat, cover and simmer very gently for about 1-1/4 hours until all the ingredients are tender and the sauce is thick. Serves 4.

Lamb and Vegetable Pie

2 tbsp lard

1 onion, chopped

2 carrots, chopped

1 stick celery, chopped

1 lb lean stewing lamb, diced

2-1/2 cups gravy

1 tbsp cornstarch

2 lbs potatoes, peeled & quartered

1/4 cup butter

Salt & pepper to tasteHeat the lard in a large saucepan and fry (saute’) the onion, carrot, and celery until browned and soft. Add the lamb and fry until sealed on all sides. Pour in the stock and season with salt and pepper. Bring to boil, then reduce the heat, cover and simmer gently for 45 minutes until the meat is very tender. If the gravy is not thick enough, mix the cornstarch to a paste with a little water, then blend into gravy and simmer, stirring, until thickened, Spoon into casserole dish (Dutch oven). Meanwhile, cook the potatoes in boiling salted water until tender, then drain and mash with most of the butter. Spoon over the lamb and dot with the remaining butter. Bake in preheated oven at 375 degrees for 30 minutes until heated through and golden brown on top. Serves 4.

Irish Beef with Guinness

2 tbsp all purpose flour

2 lb Shin of beef, chunks

2 tbsp lard

2 onions, sliced

4 carrots, sliced

2/3 cup Guinness stout

2/3 cup water

1 tbsp chopped fresh parsley

Salt & pepper to tasteSeason the flour with salt and pepper. Toss the beef in the seasoned flour, shaking off any excess. Heat the lard in a large, heavy-based saucepan and fry (saute’) the beef until lightly browned on all sides. Remove from the pan. Add the onions to the pan and fry until soften but not browned. Add the beef and carrots, stir well, then pour in the Guinness and water. Bring to the boil, then reduce the heat, cover and simmer gently for 1-2 hours until meat is tender and the sauce is thick, adding a little more liquid during the cooking if necessary. Serves 4.

Spiced Irish Beef

1/2 cup salt

2 tsp ground cloves

2 tsp ground black pepper

2 tsp allspice

2 tsp cinnamon

2 tsp mace

2 tbsp molasses

2 tbsp soft brown sugar

6 lbs Topside or sliver side beef

2/3 cup GuinnessMix together the salt, spices, molasses, and sugar. Place the beef in a small, deep bowl and add the spice mixture, rubbing it into the meat. Cover and place in the fridge for 1 WEEK, rubbing the mixture into the meat once or twice a day. Tie the meat into a neat shape and place it in a heavy based saucepan. Pour over the Guinness, then add enough water to cover the meat. Bring to the boil, reduce the heat, cover and simmer gently for 5 hours until the meat is tender. Leave meat cool in the liquid, then remove and leave to drain. Serve thinly sliced. Serves 12.

Dublin Bay Prawns in Whiskey Cream

2 tbsp butter

1 lb prawns (shrimp) cooked

3 tbsp Irish Whiskey

2/3 cup light cream

Salt & pepper to tasteMelt the butter in a large frying pan, add the prawns and stir together quickly until coated in butter. Add the whiskey and cook for 1 minute to evaporate the alcohol.

Add cream, season with salt and pepper then heat through before serving. Serves 4.

Herring in Oatmeal with Red Apples

4 herrings, cleaned

1 tbsp all purpose flour

1 egg, beaten

1/2 cup oatmeal

3 tbsp oil

2 red apples, cored and sliced into rings

Salt & pepper to tasteRemove the heads, tails and fins from the herrings. Season with the flour with salt and pepper; toss the fish in the flour, shaking off the excess. Dip the herrings in beaten egg, then coat with oatmeal. Heat oil in a heavy-based frying pan and fry the herrings for about 5 minutes on each side. Remove from the pan and drain on kitchen paper towels, keeping hot. Add apple slices to the hot pan and fry for a few seconds until just golden, turning once. Arrange the herring on a warmed serving dish, top with apple slices and garnish with parsley sprigs. Serves 4.

Boxty: One of the most traditional of Irish potato recipes, Boxty can be served on its own or as part of an Irish farmhouse breakfast with bacon and black pudding, sausages and eggs. A famous Irish rhyme sung by housewife’s, shows the importance once given to the dish by the traditional Irish Cook:

Boxty on the griddle,

Boxty in the pan.

If you can’t make boxty,

You’ll never get a man!1 cup potato, peeled and grated

1 cup mashed potato

1 cup all-purpose flour

1/2 tsp baking powder

1 egg, slightly beaten

Salt and pepper to tasteMix together the grated and mashed potatoes, flour, and baking powder and season with salt and pepper. Work in the egg, then enough of the milk to make a soft dough. Melt a little butter on a hot griddle and drop in spoonfuls of the dough. Fry over medium heat for about 2 minutes until browned on the underside, then flip over and brown on the other side. Serve with butter and applesauce. Serves 4.

Colcannon: These rich Irish potatoes are served in my home on special occasions and holidays.

1 lb potatoes ,peeled and quartered

1 lb cabbage, thinly shredded

1 leek, chopped

2/3 pt heavy cream

1/2 cup sweet butter, melted

Salt and pepper to taste

Pinch of maceCook potatoes and cabbage separately in boiling water until tender, then drain well. Meanwhile boil the leek in the cream for about 5 minutes. Mash the potatoes until fluffy; stir in the cabbage. Beat in the cream and leek; season to taste with the salt and pepper and mace. Spoon into individual bowls and make a well in the center of each. Fill the wells with the melted butter and serve at once. Serves 4.

Irish Cabbage with Bacon

1 savory cabbage, halved and tough stem removed

8 oz lean bacon

4 allspice berries

Salt & pepper

1-1/4 cup chicken stockCook the cabbage in boiling salted water for about 15 minutes, then drain well and chop. Line the base of a Dutch oven with half the bacon and place the cabbage on top. Add the allspice berries and season with salt and pepper to taste. Top with the remaining bacon and pour over just enough stock to cover the cabbage. Cover and simmer gently for 45 minutes until the ingredients are very tender and almost all the stock has been absorbed.

Kale with Cream and Nutmeg

1 lb curly Kale

2 tbsp butter

2 tbsp heavy cream

3 tbsp vegetable stock

Pinch grated fresh nutmeg

Salt and pepper to taste

Nutmeg for garnishRemove any tough stalks from the kale and wash it well, then place it in a large saucepan with only the water that is clinging to the leaves. Cover and cook very gently for about 10 minutes until tender. Drain off any excess water and chop finely. Return the kale to the saucepan with the butter, cream, stock and pinch of nutmeg, seasoning to taste with salt and pepper. Mix well over medium heat until all the ingredients are well combined and the liquid has reduced by half. Serve hot, sprinkle with a little more nutmeg. Serves 4.

Irish Swede Pudding

1 lb Swede (rutabaga), diced

1/4 cup butter

3 tbsp fresh whole meal breadcrumbs

3 tbsp milk

1 egg, lightly beaten

Pinch of ground cinnamon

Pinch of sugar

Salt and pepperCook the Swede in boiling salted water for about 10 minutes until tender, then drain and mash. Mix in half of the butter and all the remaining ingredients, seasoning to taste wit the salt and pepper. Spoon into an ovenproof dish; dot with the remaining butter. Bake in preheated oven for 45 minutes at 350 degrees. Serves 4.

Irish Style Potato Soup

4 tbsp butter

2 medium yellow onions, peeled and sliced

2 lbs potatoes, peeled and sliced

3 cups milk

5-1/2 cups chicken stock

1/4 cup chopped fresh chives

1/2 tsp celery seeds

1/4 tsp dried thyme, whole

1 cup light cream

Salt and pepper to taste

Roux:

2 tbsp all-purpose flour

1/2 cup chopped fresh chives

6 slices lean bacon, crisply fried and choppedHeat a 6-8 quart stockpot, add the butter and onion, and cook gently. Do not let the onion brown. Add the peeled and sliced potatoes, milk, and stock. Add the herbs. Cover and cook gently for about an hour. Prepare a roux: melt the butter in a small saucepan and whisk in the flour. Let the flour and butter mixture bubble for 2 minutes on medium-low heat, stirring constantly. Thicken the soup with the roux, whisking carefully to avoid lumps. Cook for 5 to 10 minutes and then puree’ the soup in a food processor. Add the cream and gently reheat, but do not boil. Season with the salt and pepper. Serve with chopped fresh chives and crisply fried bacon as garnish.

Vegetable Skink: Sink is a Gaelic term for broth, and this particular recipe makes a flavoursome broth with mixed vegetables

3 celery sticks, chopped

6 lettuce leaves, chopped

4 oz frozenpeas

4 scallions, chopped

3 cups vegetable stock

3 sprigs of parsley

1 sprig thyme

A few chive stalks

1 bay leaf

1 egg yolk

5 tbsp heavy cream

1 tbsp fresh chopped parsley

Salt & Pepper to tastePlace the vegetables and stock in a large saucepan. Tie the parsley, thyme, chives and bay leaf together in a piece of cheesecloth, then add to the pan. Bring to the boil, reduce the heat, then cover and simmer for 30 minutes until the vegetables are tender. Discard the herbs. Blend together the cream and egg yolk, stir it into the soup and heat through gently without boiling. Season to taste with salt and pepper and serve sprinkled with the chopped fresh parsley. Serves 4.

Irish Pea and Ham Soup

2 tbsp butter

1 onion, chopped

2-1/2 cups vegetable stock

2-1/2 cups milk

8 oz cooked, diced potatoes

6 oz frozen peas

1 cup cooked ham, diced

1 tbsp chopped fresh parsley

1 tbsp light cream

Salt & pepper to tasteMelt half the butter in a large saucepan and fry (saute’) the onion until soft but not browned. Add the stock and milk and bring to the boil. Add the potatoes and peas, reduce the heat and simmer for about 15 minutes until the peas are tender and the potatoes are beginning to fall apart. Puree’ in a food processor or blender, then return to the pan and stir in the ham and parsley. Season with salt and pepper and stir in the cream. Heat through before serving. Serves 4.

Turnip Soup Irish Style

2 tbsp lard

4 oz bacon rashers

1 onion, chopped

1 potato, peeled and chopped

1 lb turnip, chopped

5 cups vegetable stock

Salt and pepper to tasteMelt the lard and fry (saute’) the bacon and onion until soft but not brown. Add the potato and turnip and fry, stirring, until all the ingredients are browned and well mixed. Add the stock and season with salt and pepper. Bring to the boil, then reduce the heat, cover and simmer gently for about 20 minutes until all the vegetables are cooked. Serves 4.

Irish Soda Bread

8 cups all-purpose flour

1 tsp baking soda

1 tsp salt

2-1/2 cups buttermilkMix together the flour, baking soda, and salt and make a well in the center. Gradually add just enough buttermilk to mix to a soft, but not sticky dough and knead lightly until smooth. Shape into a 9-inch round, place on a greased cookie sheet and cut a deep cross in the top. Bake in pre-heated 400 degree oven about 1 hour until risen and golden and the bread sounds hollow when tapped on the base. Makes 1 (2-lb) loaf.

Potato Farls: The Irish love to serve potato bread with their hearty breakfasts. “Farl” actually means “quarter”, although you can cut the dough into rounds if you prefer. You can also add some fresh herbs to the dough.

3/4 cup all-purpose flour

1/2 tsp baking powder

Pinch of salt

2 tbsp butter

8 oz mashed potatoes

2 tbsp milkMix together the flour, baking powder and salt in a bowl, then, using your fingertips, rub in the butter until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. Stir in the mashed potatoes and enough of the milk to make a soft but not loose dough. Roll out on a lightly floured surface to a round about 1-inch by 1/2-inch thick and mark into quarters, without cutting right through the base. Place on a greased cookie sheet and bake in a preheated 400 degree oven for 20 minutes until golden. Alternatively, Place on a greased griddle and cook for about 10 minutes over medium heat. Serve with plenty of butter. Serves 4.

Irish Butter Scones

1/3 cup butter

2 cups self-rising flour

1/4 cup caster sugar

1 egg, lightly beaten

3 tbsp buttermilk

Pinch of saltUsing your fingertips, rub the butter into the flour and salt until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. Stir in the sugar. Gradually work in the egg and enough of the buttermilk to make a soft, but not sticky, dough. Roll out the dough on a lightly

floured surface to 1-1/4 inch thick and cut into rounds with a 2-inch pastry cutter. Place the scones on a greased baking sheet and bake in a preheated 400 degree oven for 6 to 10 minutes until well risen and golden brown. Cool, then split and spread with jam or butter. Serves 4.

Chocolate Irish Soda Bread Pudding with Guinness Stout Ice Cream

2 loaves of Irish Soda Bread

4 oz butter, melted

6 eggs

1/2 cup brown sugar

1/4 cup raisins

1 qt heavy cream

8 oz semi-sweet chocolate, choppedCut l loaf of bread into cubes. Process the remaining half in a food processor. Place bread cubes and crumbs in a bowl and cover with melted butter, toss and set aside. Place cream in a saucepan and bring to a boil. Place chopped chocolate in a bowl and set on top of the cream and let it act as a double boiler to melt the chocolate. In another bowl beat eggs and sugar until pale and thick. When the cream comes to a boil pour it over the chocolate whisking quickly. Then temper the chocolate-cream mixture into egg mixture. Mix in the raisins. Pour this mixture over the bread, mix well, and let it soak overnight. There should be a sense of moistness. If the mixture looks dry, add another 1/2 cup of heavy cream. Preheat oven to 375 F. Butter a 9-inch cake pan. Pour mixture into pan. Place in a hotel pan and fill 3/4 up the sides with water (cold). Bake for 1/2 hour at 375 F. Turn pan, reduce heat to 325 F and bake for another 1/2 hour or until a toothpick inserted comes out dry. Top with Guinness Stout Ice Cream.

Guinness Stout Ice Cream

3 egg yolks

2 tbsp sugar

1 cup milk

2 tbsp heavy cream

1 pt Guinness StoutFirst, if the bowl of your ice cream maker has to be frozen, make sure you do so. In a saucepan bring the pint of Guinness to a boil and let it reduce to about half of to concentrate the flavor. Whip the egg yolks and sugar until pale and thick. In another saucepan bring the milk and cream to a boil. Pour the boiling milk mixture over the yolks and whisk constantly, until it thickens just enough to coat a spatula. Do not allow the mixture to boil. Pass through a fine strainer or 2 layers of cheesecloth. Cover loosely and quickly place in an ice bath, whisking the Guinness Stout reduction. Churn in an ice cream machine according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Blackcap Pudding

8 oz blackcurrants

1/2 lemon rind grated, and juice

1/4 cup caster sugar

1 cup all-purpose flour

½ tsp baking powder

2 cups breadcrumbs (white)

2 eggs, beaten

1-1/4 cups milkRinse the blackcurrants and place in a saucepan with only the water that is clinging to them. Add the lemon rind and juice and half the sugar and simmer gently for 6 minutes, then spoon into greased 5-cup stainless bowl. Mix the remaining sugar, with the flour & milk, leave to stand 15 minutes. Spoon over the blackcurrants, then cover with pleated wax paper and foil. Place the stainless bowl into a large saucepan and pour in enough boiling water to come halfway up the sides of the stainless bowl and steam for 2 to 2-1/2 hours until set, topping up the boiling waster as necessary. Carefully loosen the edges of the pudding; turn it out on to a serving plate. Top with whipped cream. Serves 4.

Whiskey Trifle

1 (8-inch) sponge cake, chopped

3 tbsp sweet sherry

3 tbsp Irish Whiskey

4 tbsp raspberry jam

1-1/4 cup thick custard

1-1/4 cup heavy creamPlace cake pieces in the base of a serving bowl. Stir in the jam and pour over the sherry and whiskey and let it soak in. Stir in the jam and pour the custard over top. Whip the cream until stiff and spread over the custard. Chill before serving. Serves 4.

Porter Cake

1-1/3 cup currants

2 cups raisins

2 cups sultanas

1 cup porter

1 cup butter

1 cup soft brown sugar

4 cups all-purpose flour

1/4 cup chopped mixed candid peel

1 tsp apple pie spice mix

1 lemon rind, grated

3 eggs

1 tsp baking sodaMix the currants, raisins and sultanas with the porter and leave to soak until plump. Cream together the butter and sugar until light and fluffy. Mix the flour, mixed peel, spice and lemon rind. Gradually add them into the butter mixture alternately with the eggs, stirring well after each addition. Pour off a little of the porter from the fruit and warm it slightly. Stir in the baking soda; pour over the fruit. Stir, then mix the fruit into the remaining ingredients. Spoon into a greased and lined 9-inch cake pan. Bake in a preheated 350 degree oven for about 1-1/2 hours until a skewer inserted in center comes out clean. Cover the top with wax paper for the last 30 minutes. Makes one 9 inch cake. Porter is less strong than stout, you may replace it with Guinness or Murphy’s. Use half the stout amount listed.

Yellow Man

1-1/2 cups light corn syrup

1 cup soft brown sugar

2 tbsp butter

2 tbsp distilled malt vinegar

1 tbsp baking sodaPlace all the ingredients except the baking soda in a large, heavy saucepan and heat gently until the sugar and butter have melted. Bring to a rapid boil and boil until the syrup has reached 289 degrees on the candy thermometer. Stir in the baking soda; the mixture will form. Pour onto a greased work surface and leave until cool enough to work with. Now with greased hands, fold the mixture from the edges to the center and pull. Repeat until it turns yellow. Allow to cool and harden, then break into chunks using a toffee hammer.

Irish Potatoes

3 lbs butter

3 lbs cream cheese

18 lbs confectioners’ sugar

or

1-1/2 lbs butter

1-1/2 lbs cream cheese

9 lbs confectioners’ sugar

or

1 lb butter

1 lb cream cheese

6 lbs confectioners’ sugar

or

1/2 lb butter

1/2 lb cream cheese

3 lbs confectioners’ sugarBlend butter and cream cheese together thoroughly. Add a little vanilla to taste. Gradually mix in confectioners’ sugar until very thick. Chill thoroughly in refrigerator. Roll in balls and coat balls with cinnamon. If you like, you can add sweetened shredded coconut to mix before chilling & rolling. It adds “body” and they have less of a tendency to get soft when left out at room temperature.

Irish Coffee

2 cup hot strong coffee

2 tsp soft brown sugar

4 tbsp Irish Whiskey

4 tbsp heavy creamWarm two Irish Coffee glasses by filling them with hot water and emptying them, then filling them with almost boiling water and emptying them again.

Pour the coffee into glasses, add the sugar and stir to dissolve, then add the whiskey. Hold a spoon bowl-side up over the top of the coffee and pour the cream on to the back of the spoon so it flows on to the top of the coffee, forming a thick layer. Serves 2.

Hot Whiskey

1/2 cup Irish Whiskey

2 lemon slices

2 whole cloves

2 tsp caster sugarWarm two whiskey glasses by filling them as above. Place the whiskey, lemon and cloves in the glasses, then half-fill with boiling water and stir in the sugar to taste. Makes 2 servings.

The Irish Breakfast is called "fry" and is served all day. Porridge; bacon; pork sausage; smoked salmon; calves' liver; eggs scrambled, fried, boiled and poached; pudding black and white (sausages); drisheen (blood sausage); crubeens (pigs' feet) lamb chops; lamb kidney; mushrooms, tomatoes, and onions finnan

haddie; kippers; kedgeree (smoked haddock) with rice and chopped hard-boiled eggs with cream and butter are the staples of the Irish diet.But the Irish Breakfast is something that is and has been talked about for centuries by both the tourist and the Irish laborer. Fry is a social event in Ireland and no matter how many people show up, it is never a big deal to set one more plate at the kitchen table.

The Irish Breakfast ("Fry")

8 slices Irish bacon

8 Irish sausages

4 slices black breakfast pudding

4 slices white breakfast pudding

4 eggs

4 medium tomatoes

Freshly ground pepper.Over low heat, fry bacon, turning frequently until done to taste. Irish bacon should remain soft rather than cooked to hard or crisp. Remove and drain on paper towels. Place sausage in the pan and brown on all sides; Remove and drain on paper towels. Cut the tomatoes in half and fry them in the bacon fat, cut side down, with slices of pudding. Remove and keep hot. Cook eggs to order; fried, poached or scrambled. Add freshly ground pepper to taste. Add grated cheese to taste if eggs are scrambles. Divide equally on four plates and serve with Irish Brown soda bread with butter and marmalade.

Irish Brown Bread

4 cups whole wheat flour, preferably stone ground

2 cups unbleached white flour

1 tsp baking soda

1/2 tsp salt

2 cups good buttermilkPreheat oven to 400 F. Mix the flours, baking soda and salt in a bowl. Make a hole in the middle and add the milk, stirring vigorously, to make a trickish dough, not too floppy. Mix well; turn out onto a floured board; make a round cake 2 inches high and 7 inches across. Warm a cast iron skillet in the oven for 3 minutes. Take it out, grease and flour it. Add the dough and with a wet knife make a cross cut on top. Bake about 40 minutes, or until cooked through. Remove from oven and wrap loaf in clean tea towel. Cool for 5 to 6 hours.

Bacon-Dill Scones (Traditional Irish favorite)

6 slices Irish bacon

2 cups all-pourpose flour

1 tsp baking powder

1/4 tsp baking soda

1/4 tsp salt

1/4 cup butter, cut into small pieces

2/3 cups good buttermilk

2 tbsp chopped, fresh dill

1 tsp grated lemon zest

1 egg, lightly beatenPreheat oven to 425 F; coat baking sheet with cooking spray. In large skillet over medium-high heat cook bacon until crisp, 6 to 8 minutes. Transfer bacon to paper towels; cool 5 minutes. Cut into 1/2" pieces; set aside. Combine flour, baking powder, soda and salt. With pastry blender or 2 knives cut in butter until mixture resembles coarse crumbs. Stir in buttermilk, dill, zest and reserved bacon until combined and dough comes together. Divide dough in half. On lightly floured surface form each half into 5" circle. Cut each circle into 4 wedges; transfer to baking sheet. Brush tops with egg. Bake 15 minutes or until

lightly browned. Cool on pan on rack 5 minutes. Remove from pan, serve or

let cool completely and serve.You may email us by clicking on the link above.

And while you are here, please sign our guestbook :-)

These beautiful graphics are courtesy of Pat:

Webpage designed and maintained by Leilani Devries.